Step one of learning Japanese is to memorise the hiragana characters. But how do you learn hiragana? Fortunately, there are a lot of methods and resources to help you take this first step. Unfortunately, the choice can be bewildering.

Which method should I pick? Which resources should I use? Am I doing it all right?

All these questions and more are likely to crowd your mind. So, let’s take a breath, look at some facts and get answers to those questions.

What is hiragana?

Before you can learn something, you need to know what it is.

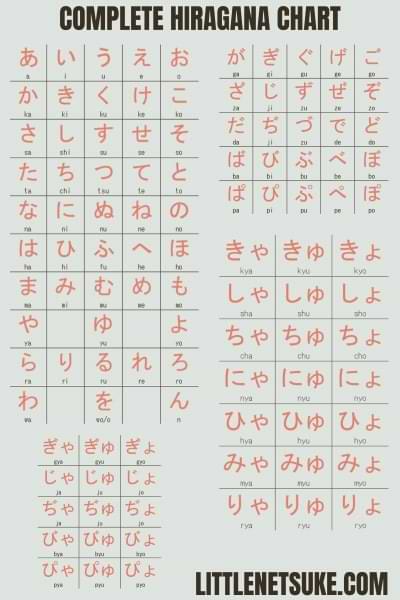

Simply put, hiragana is 46-character-long syllabary.

That is to say that it is a collection of characters that represent the syllables of Japanese. Unlike our alphabet, hiragana characters can represent a collection of sounds. For example, the hiragana character す would be written as ‘su’ in the Roman alphabet.

Another helpful feature is that the sounds a hiragana character makes are consistent, unlike our alphabet.

Why is Hiragana Important?

Japanese is written using three scripts. They are hiragana (ひらがな), katakana (カタカナ) and kanji (漢字). The reason for this and their different uses is probably best left for another time.

Suffice it to say, while hiragana is only one piece of the Japanese writing symbol, it is the single most important piece.

That is because of its uses.

- No less than 37% of written Japanese is hiragana.

- Dictionary entries are written in hiragana and organised by their first hiragana character.

- The grammar of Japanese is written in hiragana.

- Kanji reading can be illustrated using hiragana floating above them (furigana).

It is fair to say that the 46 characters of hiragana are the key to the Japanese language.

When should I learn hiragana?

The consensus among learners and teachers of Japanese is clear. Learn it immediately.

While it may seem frustrating to plough hours into learning all these strange characters, putting it off will slow your progress.

That is because of the alternative. Romaji.

The Problem with Romaji: 1

Romaji refers to the use of the Roman alphabet to illustrate the pronunciation of written Japanese. In essence it is a middle man. As with all middlemen there is a cost.

That cost is native language interference. Because Romaji looks like the alphabet we use every day, it can be easy to make simple pronunciation mistakes.

This is illustrated by the way we say ‘Tokyo’ in English. The Anglicised pronunciation uses a short o sound like that in ‘toe’ as well as adding a vowel sound between the k and y. Thus, we end up with ‘Toe-key-yo’ in English.

Part of the problem here is that English has more sounds to choose from than Japanese. For example, an English o can be like that in ‘to’ or ‘toe’ or ‘thought’. Japanese is far more consistent.

In Japanese Tokyo is pronounced with a long o sound similar to that in ‘thought’ and doesn’t insert an invisible vowel sound between the k and y. So, if we’re following the Japanese pronunciation of their own capital should say ‘Toukyou’.

As you can see, learning Japanese with Romaji could ruin your Japanese pronunciation.

But that isn’t all.

The Problem with Romaji: 2

When learning to read in any language, whether your mother tongue or a foreign language, your brain develops pattern recognition in that language.

In time, rather than focusing on individual letters, you see whole words instead. That’s why you can still read this:

“Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrgde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are … Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe.”

By learning using Romaji you are training your brain to recognise a pattern it won’t see once you have learnt hiragana. I think the inefficiency is obvious.

In fact, once proficient in reading Japanese it is much harder and slower to read Japanese in Romaji than it is to read in hiragana and the rest.

Besides, learning hiragana first means all further study is reinforcing this skill.

How should I learn hiragana?

Let’s get on with it then, you may be thinking. Indeed, that’s why the internet is full of articles that promise to teach you hiragana at lightning speed.

Before you rush off, which is better learning quickly or learning effectively?

I believe it is the latter.

Provided you reach the goal of memorising hiragana, there is no right or wrong way to achieve it. But that doesn’t mean each way is as effective.

What is effective for a given person is to some extent subjective. It can depend on how you like to study, the sorts of strategies that have worked in the past, the amount of spare time you have and so on.

However, there are helpful tricks and techniques common to us all. Having a basic idea of how the brain works can point to better ways to study.

How memory works: A very basic guide

A quick disclaimer, I am no scientist. Instead, this is my understanding of how memories work based on my research.

When boiled down, memory formation is a three-step process.

Step 1; encoding. This is when your brain consciously perceives information. This could include sounds, images, feelings, smells et cetera.

Step 2; storage. The brain stores the information perceived in step 1. Signals travel between neurons and this activity makes memory pathways.

Step 3; recall. Stored information is recalled by revisiting the pathways created in step 2. This strengthens the pathways and so extends the storage of the information.

One of the most important scientific findings is that the more senses that are involved the stronger the memory. This is known as semantic encoding. It works because more signals are sent between more neurons forming a larger, and thus stronger, pathway.

Armed with this knowledge, let’s evaluate the different methods of learning hiragana.

Rote Memorisation

This technique has a reputation for being monotonous, so it may seem like a bad place to start. However, it can be an effective strategy if used correctly.

Researchers are clear that rote memorisation works best for foundational knowledge that doesn’t need interpretation. Information like dates, multiplication tables or 46 characters of a foreign script.

Contrary to popular opinion, rote memorisation doesn’t have to mean endlessly reading and rereading the hiragana table.

For example, writing by hand has been shown to trigger the part of the brain (RAS) that stimulates concentration. So rather than skipping learning how to write the characters, as some recommend, it’s more effective to weave this trick into any rote memorisation.

Additionally, an easy way to involve another sense is to recite the characters’ sounds as you write them.

Pros and Cons

The advantage of rote memorisation is its simplicity and familiarity. All you need is a hiragana table, pronunciation guide, paper and pen.

Also, this approach tends to mean a good awareness of the structure of the hiragana chart. As that structure is used to “alphabetise” things in Japan, knowing it well can be pretty handy if you want to live and work in Japan.

However, a major drawback is the risk of over drilling. This can lead to a context dependant recall, so you have to work through the chart in order to remember the characters pronunciation. This is a real problem when trying to write in Japanese.

This issue can be averted by using randomised flashcard testing.

Example Approach

- Start with line one of the hiragana chart.

- Review the pronunciation of each character.

- Practise each pronunciation until it feels more comfortable.

- Review the stroke order for each character.

- Write the first character and recite its pronunciation.

- Repeat until it feels more comfortable.

- Cover any examples of the character and repeat a few more times.

- Make a flashcard of that character (character on one side and pronunciation on the other)

- Review the card in both directions.

- Repeat for the entire hiragana chart

You can create flashcards using an SRS program like Anki or a Leitner box system for the more technophobic.

Mnemonics

From zero to hero. In contrast to rote memorisation, mnemonic tricks are some of the most popular learning methods.

They’re not new either with a history of at least 2,500 years.

This approach may be familiar as the verbal tricks used at school. For example, using Roy G. Biv to learn the colours of the rainbow.

Semantic encoding can be employed here too by creating mental images. The more vivid and bizarre the better, according to research.

Let’s try with Roy G. Biv. Imagine Roy is a businessman wearing a stripped multicoloured suit. This use of imagination may help to lodge the information further in your mind.

But be careful. The visual or verbal cue must make sense to you. Getting carried away and adding lots of details may be confusing when it comes time to recall the information.

Pros and Cons

Mnemonics can be a fun way to learn hiragana, but they can also be time consuming.

While making your own will likely result in stronger memories, there are plenty of readymade examples that can be found.

The real problem here is accuracy. Because you will use English as a foundation for your mnemonics you need to make sure that they use the correct pronunciation and avoid images that are confusing.

This is especially problematic when using someone else’s mnemonics. For example, if it is based on American English pronunciation, it may not work and mislead someone who speaks a different form of English.

Example Strategy

There are many resources that use mnemonics to teach hiragana.

Two of the more popular are ‘Remembering the Kana’ by James Heisig and Tofugu’s ‘Ultimate Guide to Hiragana’.

‘Remembering the Kana’ uses ‘imaginative memory’. That is mnemonic stories. You visualise a story that contains prompts for the pronunciation and form of each character. This approach tends to divide students along marmite lines. You’ll either love it or hate it.

Tofugu’s ‘Ultimate Guide to Hiragana’ uses a mix of images, sentences and stories to help you learn to recognise the characters. There is a sound file for each character which is useful, but provides nothing for those wishing to learn to write the hiragana.

Progressive Approach

This is a niche approach that seems to be unique to the Japanese from Zero textbook series by George Trombley.

In his series Trombley makes Japanese more accessible for the average learner by avoiding longwinded grammatical explanations and a progressive approach to hiragana.

In the ‘Progressive Approach’ edition, everything is written in Romaji at the beginning. The characters are then introduced gradually and then replace the Romaji.

This means that romaji and hiragana are mixed together while romaji is phased out as you learn more hiragana.

Pros and Cons

This gradual approach avoids overwhelming students as well as providing immediate practice once characters are introduced. So, by the end you’re likely to be more proficient at actually using hiragana than with other memorisation only approaches.

One problem is that it’ll take more time to become familiar with the full chart. This locks you into the book series as hiragana knowledge is usually the minimum requirement for other Japanese textbooks.

Example Strategy

Here is an example sentence from book 1 that shows the approach taken.

“Junこさ n wa niju うごさい de す.”

Beyond Memorisation

If you’ve chosen a method already you might think that all you need to do is follow that method, but that isn’t quite right.

So far, we’ve only talked about memorising hiragana. There is a big difference between memorising them and actually being able to use them accurately and confidently. For that you need practise.

There is a seemingly infinite number of apps and worksheets and flash cards out there to help you practice and develop your hiragana ability.

Next, we’ll take a quick look at what makes good practice and then highlight some of the best resources out there.

Retrieval Practice

If you think back to the memory creation process discussed earlier, you’ll remember that the third stage is recall and that recalling a memory makes it stronger.

Enter retrieval practice.

Also known as the testing effect, retrieval practice relies on getting your brain to retrieve information, so boosting your memory.

A 2006 study showed that students who followed study sessions with a short test scored higher on later tests than students who had only studied the information.

The difference wasn’t slight. The study-test students remembered 20% more than the other students. These findings are similar to those that underpin the spaced repetition approach used by popular flash card apps like Anki or Duolingo.

Making use of this form of practice is a must for more efficient retention and confidence with hiragana. It can be as simple as writing the characters out from memory or using a study game to help reinforce the memory.

Ways to practice

Any time you use hiragana is practice, so there is no shortage of ways to practice. But here are some of the most popular ways and the best resources to use.

Apps

The Google Play store alone returns 250 android apps for learning hiragana. They range from short courses, games or testing apps.

To save you time I have cut that list down for you.

Kana Town is a great hiragana (and katakana) testing app. The testing is simple, you must type in the correct romanisation of the hiragana character displayed.

There are two test types available, SRS or mock. The mock tests do not change the SRS scores, but you are able to choose the length and contents of the test.

The SRS type is determined by the app based on your previous answers. You can add the whole table or individual lines of the table which makes this a great option to introduced practice from the very start.

Even better, it is free, so you can try it risk free.

Practice Sheets

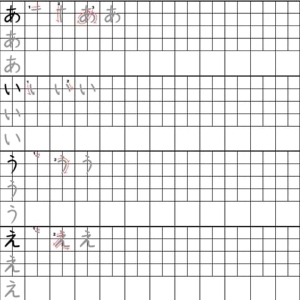

Hiragana practise sheets are an excellent way to practice writing hiragana.

Typically, the sheets will indicate the stroke order of the character, give a number of examples that you can trace over and some empty boxes for you to fill alone.

Japanese-lesson.com offers free printable sheets to use for practice. They have two sheet sets. One set of guide sheets like the sheet described above and a blank sheet for more confident practice.

Reading

You should be learning hiragana before anything else. So reading practice at this stage is not about understanding what’s written, but gaining reading fluency.

Crunchy Nihongo has 7 short stories that are great for practice. They are designed with absolute beginners in mind.

The stories are broken down into short sentences. Particles (hiragana with special grammatical function) are shown in bold to help make the sentences more digestible.

The greatest thing about these stories is that you can show and hide the sentences in Romaji and a translation. This allows you to check you are reading the characters correctly and also enjoy the story through the translation.

Once you have mastered hiragana and learnt some basic grammar and vocabulary you can come back to these stories and reread them in the Japanese. This makes this an effective practice and evaluation resource as you return and see the improvement you have made.

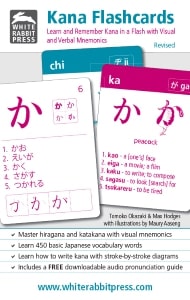

Flashcards

If you have limited time you can buy flashcards for testing your hiragana knowledge.

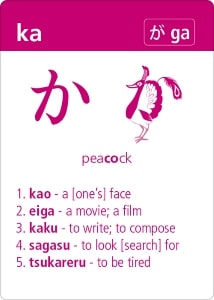

While there are several options the Kana Flashcards by White Rabbit Press are a popular choice.

The set contains both hiragana and katakana cards. The front shows a character, example words, stroke order diagram and example of the character in different fonts. The back shows the character again, a mnemonic image, English word to demonstrate the pronunciation and example words in Romaji.

However, non-American English speakers beware. The illustrative English words use American English pronunciation. As the below image shows this can be misleading for speakers of other forms of English.

There are many more resources out there and I encourage you to search for yourself if you have the time.

The Bonus Method

Before we finish, there is one more method that I want to mention.

For me, it was frustrating to spend hours learning hiragana before any of the actual language. This is one reason why the progressive approach mentioned above appeals to me.

But in my opinion using romaji as a crutch for any amount of time is best avoided. Even if it allows you to learn Japanese vocabulary and grammar at the same time.

What if there was a way to learn useful Japanese with only hiragana, while learning hiragana?

Well, I think there is.

Even if you only know the first line of hiragana you can start learning some very common words.

For example, knowing あ is like the a in father, お is like the o in organ and い is like the i in Italy, means you can read あおい; the Japanese word for blue.

If you can find common words that only contain the characters you have learned so far, you can learn vocabulary and hiragana side-by-side.

The trouble is it’s a lot of work and pretty difficult if you can’t already read hiragana. But if you could do that, there would be little point doing it.

That’s why I’ve done it for you. I have taken some of the most frequently used Japanese words and ordered them based on the hiragana chart. Each line of the chart is introduced followed by vocabulary that only uses those or earlier characters you have learned.

Following this guide, you will learn hiragana alongside 100 of the most common Japanese words. It also has short sentences to practice. Thus, you will be able to continue to other Japanese resources with greater hiragana proficiency and a vocabulary foundation.

It’s free to download.

Conclusion

Hiragana is the most important single step on the road to Japanese mastery and there are many roads that you can take.

I hope you now have a better understanding of how to learn hiragana.

Don’t forget that the route is up to you. You may take one road or multiple. Like using mnemonic tricks to get the characters into your short-term memory, then pushing them deeper with rote memorisation techniques and finally gaining fluency through practice.

You could also learn hiragana alongside basic vocabulary or mixed in with romaji and grammar.

Whatever method or methods you use, I wish you luck.

Sources:

The Rote Learning Method – What you need to know, improvememory.org

Psychology of Mnemonics, K. L. Higbee, International Encyclopaedia of the Social & Behavioural Sciences, 2001

The Science of Memory: Top 10 Proven Techniques to Remember More and Learn Faster, Melanie Pinola, zapier.com

Assessment as Learning: The Role of Retrieval Practice in the Classroom, J. Firth, M. Smith, B. Harvard, A. Boxer, 2017

Test-Enhanced Learning, Henry L. Roediger & Jeffrey D. Karpicke, Psychological Science, 2006

Writing by hand improves your memory, Emily Blatchford, Huffington Post, 2016

Using Mnemonics to Improve Your Memory, Psychologist World

A Japanese logographic character frequency list for cognitive science research, N. Chikamatsu, Behaviour Research Methods, 2000

2 Responses

I just came to say thank you, learning japanese has been one of mi biggest dreams and I just decided to start doing so, since I am currently working a full time job there’s no much time left for me to go to a school or something like that, finding your page has been an absolute delight!

Thank you so much.

Thank you for your comment. I’m glad it has been useful and I wish you the best of luck with learning Japanese!